Humans are surface dwellers, evolved to thrive within a very slim portion of Earth’s atmosphere. We’ve come to recognize the rich diversity that spirals down into the soil, rock, ice and ocean depths, but the space above our highest mountains is often dismissed as a mere runway to the stars—a place for the occasional Himalaya-soaring goose, bust mostly the realm of human technological accession.

But the wide blue yonder is far from lifeless. It’s a realm where spiders and other invertebrates sail to dizzying heights on silken threads, amid waves of “aeroplankton” microbes: viruses, bacteria, fungi and more.

Chelsea Wald’s recent Nautilus article “The Surprising Importance of Stratospheric Life” provides an excellent look at the complexities of life in Earth’s atmosphere. In particular, she raises some real mind-bending questions about the process by which many microbes ascend to the troposphere and stratosphere, suffer the cleansing wrath of UV radiation, and then return to Earth in the form of condensation nuclei in the heart of ice crystals. This jaunt through hostile environmental heights, according to Wald, may serve as a “pre-selection filter” to ensure only the hardiest lifeforms descend back down to terrestrial environments ranging from fertile to down-right cryogenic.

Of course, to confront all of this invisible atmospheric life is to raise questions about other worlds. Might other atmospheres within our solar system harbor atmospheric life as well?

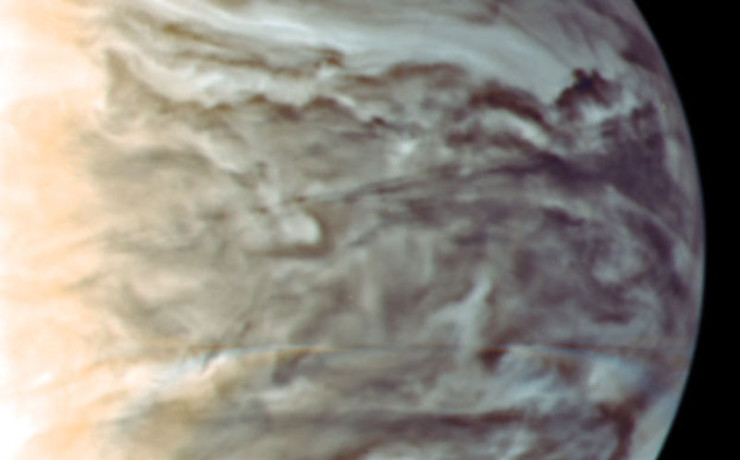

Venus in particular has intrigued scientists for decades, as its atmospheric temperatures are more far tolerable than its hellish surface. Carl Sagan theorized we might terraform the planet via an atmospheric injection of algae, while some contemporary scientists believe that Venusian microbes may have actually seeded Earth. The hypothetical process would have required cloud bacteria to well up into Venus’s upper atmosphere and then peel off on the solar wind, surviving a hostile—but reasonably short—journey to Earth.

Either way you shake it, Earth-to-Venus or Venus-to-Earth, panspermia is a wrought with potential complications and scientists disagree on the likelihood of either venture working out. But we do know that life itself is hardier and far more resilient to atmospheric heights than the human form would have us believe. What single-celled organisms, unbeknownst to us, might even now cling to life within the sulfuric acid clouds of Earth’s inner sibling?

Robert Lamb is a science podcaster and writer who occasionally commits acts of fiction. Tweet him @vomikronnoxis and explore more of his work at rjlamb.com and stufftoblowyourmind.com.